當(dāng)前位置: Language Tips> 雙語新聞

American academic who invented revolutionary theory of 'human economics' and starred alongside Selena Gomez in The Big Short wins the Nobel Prize

分享到

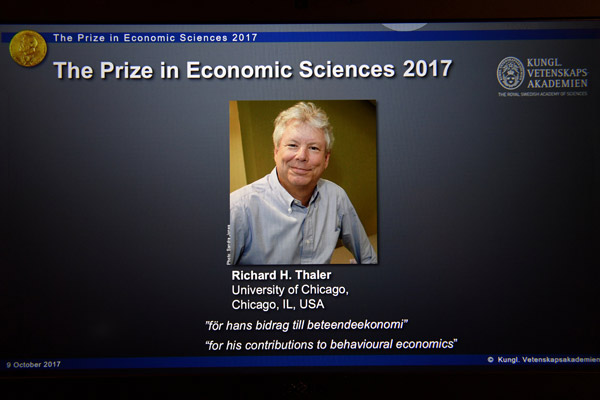

瑞典皇家科學(xué)院9日宣布,將2017年諾貝爾經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)獎(jiǎng)授予美國經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)家理查德?H?塞勒(Richard H. Thaler),“以表彰他對(duì)行為經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)的貢獻(xiàn)”。

Peter Gardenfors, member of the committee for the Economics Prize said, Thaler's achievements successfully integrated economics and psychology, as he made economics "more human." And his theories "help people make better economic decisions."

諾貝爾經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)獎(jiǎng)委員會(huì)成員皮特?加登福斯稱,塞勒的研究成果成功地將經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)和心理學(xué)整合在一起,讓經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)更“人性化”。他的理論“幫助人們做出更好的經(jīng)濟(jì)決策”。

塞勒1945年出生在美國,是行為經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)之父,現(xiàn)執(zhí)教于芝加哥大學(xué)商學(xué)院,同時(shí)在國民經(jīng)濟(jì)研究局主管行為經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)的研究工作。

塞勒還是一家基金公司的創(chuàng)始人,專注美國小企業(yè)股。在他的行為經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)理論下,公司替摩根大通管理的一只基金表現(xiàn)優(yōu)異,2015年基金規(guī)模激增1倍至37億美元,目前資產(chǎn)總規(guī)模已達(dá)60億美元。

不會(huì)演戲的經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)家不是好股神,如果你看過獲得2016年奧斯卡最佳改編劇本獎(jiǎng)的電影《大空頭》,一定會(huì)覺得這位新晉諾貝爾獎(jiǎng)得主有些眼熟。

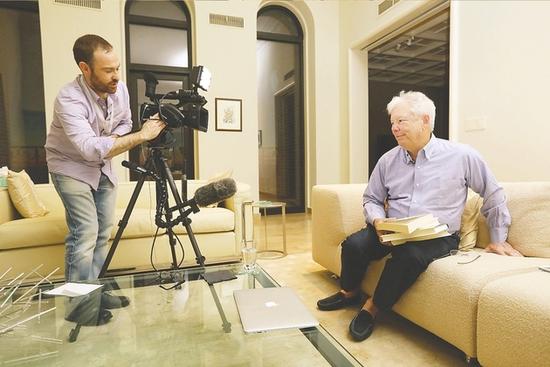

Thaler's work earned him a glamorous foray into the movie business when he made a cameo appearance, alongside Christian Bale, Steve Carell and Ryan Gosling, in the 2015 movie 'The Big Short' about the credit and housing bubble collapse that led to the 2008 global financial crisis.

塞勒曾憑借其成就得到一個(gè)進(jìn)軍電影業(yè)的機(jī)會(huì),他在2015年的《大空頭》中客串了一個(gè)小角色,和克里斯蒂安?貝爾、史蒂夫?卡瑞爾、瑞恩?高斯林同框出鏡。這部電影講述的是引發(fā)2008年全球金融危機(jī)的信貸與房地產(chǎn)泡沫崩潰。

In his cameo, he appeared in a scene alongside pop star Selena Gomez to explain the 'hot hand fallacy,' in which people think whatever's happening now is going to continue to happen into the future.

在塞勒客串的一幕中,他出現(xiàn)在流行歌手賽琳娜?戈麥斯旁邊,解釋著“熱手效應(yīng)”,這個(gè)理論說的是人們認(rèn)為現(xiàn)在發(fā)生的一切將來還會(huì)繼續(xù)發(fā)生。

用塞勒徒弟、中歐國際工商學(xué)院金融學(xué)副教授余方的話來評(píng)價(jià)塞勒的學(xué)術(shù)風(fēng)格,那就是有點(diǎn)“非主流”,“總跟別人做的研究不太一樣”。

作為一位傳統(tǒng)學(xué)術(shù)理論的挑戰(zhàn)者,塞勒認(rèn)為:人們的行為并不像傳統(tǒng)經(jīng)濟(jì)學(xué)理論中認(rèn)為的那樣理性。

Thaler has incorporated psychologically realistic assumptions into analyses of economic decision-making. By exploring the consequences of limited rationality, social preferences, and lack of self-control, he has shown how these human traits systematically affect individual decisions as well as market outcomes.

塞勒將心理學(xué)上的現(xiàn)實(shí)假設(shè)整合進(jìn)經(jīng)濟(jì)決策分析中。通過探索“有限理性”、“社會(huì)偏好”和“自制力缺乏”等因素的影響,揭示了這些人性特征對(duì)個(gè)體選擇和市場(chǎng)結(jié)果產(chǎn)生的系統(tǒng)性影響。

聽起來太高大上?下面我們將用盡量通俗的語言來介紹塞勒的主要理論:

Limited rationality

有限理性

Thaler developed the theory of mental accounting, explaining how people simplify financial decision-making by creating separate accounts in their minds, focusing on the narrow impact of each individual decision rather than its overall effect.

塞勒創(chuàng)建了“心理賬戶”理論,闡述了人們是如何通過在內(nèi)心創(chuàng)建不同的賬戶來簡化經(jīng)濟(jì)決策的:人們會(huì)聚焦于單個(gè)決策的狹隘影響,而不是它們的總體效果。

舉例說明:

We may have a “vacation” budget in our heads, and a “household maintenance” budget, and we tend not to mix them. If we get an unusually good deal on our airfare to Hawaii, we won’t use the savings to have the carpets cleaned; we’ll spend more at the bar on our vacation, keeping the money in the appropriate bucket.

我們腦海里有一筆“度假預(yù)算”和一筆“家庭維護(hù)預(yù)算”,我們通常不會(huì)將兩者混在一起。如果我們能以特別劃算的價(jià)格買到飛往夏威夷的機(jī)票,我們不會(huì)把省下的錢用來清潔地毯;我們度假時(shí)會(huì)在酒吧花得更多,讓這筆錢花在原本的預(yù)算上。

He also showed how aversion to losses can explain why people value the same item more highly when they own it than when they don’t, a phenomenon called the endowment effect.

塞勒還向我們介紹了如何用厭惡損失來解釋為什么人們擁有某件東西時(shí),會(huì)比沒有的時(shí)候更高估其價(jià)值,即“稟賦效應(yīng)”。

其實(shí)“稟賦效應(yīng)”在生活中有很多體現(xiàn),比如下面這個(gè)經(jīng)典的擲硬幣打賭的例子:

In the first case, you are offered the chance to bet on the toss of a coin: You can win $10 if you call the coin toss correctly, or lose $10 if you call the toss incorrectly. Most people will decline the bet.

在第一種情況下,你有機(jī)會(huì)玩兒擲硬幣打賭:如果你猜對(duì)可以贏得10美元,如果你猜錯(cuò)就會(huì)輸?shù)?0美元。大多數(shù)人會(huì)放棄這個(gè)賭注。

In the second case, a bet is described differently: You are told that you are about to lose $10, but there’s a 50-50 chance you could come out with no loss—but with the prospect of a $20 loss if the coin toss works against you. That’s really the same bet as in the first example, but framed as loss avoidance rather than seeking a gain. People are much more likely to take the second bet; they will take larger risks to try to avoid a loss.

在第二種情況中,賭局的描述有所不同:你被告知將輸?shù)?0美元,但有50%的機(jī)會(huì)不輸錢,不過如果猜錯(cuò)的話將輸?shù)?0美元。這和第一個(gè)賭局是相同的,但卻被視為是在避免損失,而不是尋求利益的。人們更傾向于參加第二個(gè)賭局,冒更大的風(fēng)險(xiǎn)以盡力避免損失。

Social preferences

社會(huì)偏好

Thaler’s theoretical and experimental research on fairness has been influential. He showed how consumers’ fairness concerns may stop firms from raising prices in periods of high demand, but not in times of rising costs.

塞勒關(guān)于公平的理論和實(shí)驗(yàn)研究很有影響力。他稱,消費(fèi)者對(duì)公平的關(guān)注會(huì)阻止公司在需求增加的時(shí)候漲價(jià),但卻不會(huì)阻止公司在成本上升時(shí)漲價(jià)。

還是用一個(gè)通俗易懂的例子來說明:

Let’s say you run a building supply company located in a hurricane warning area, and everyone is coming in to buy plywood. It would be bad practice to raise prices with a sign that says: “We have raised our prices so that plywood is only bought by those who really need it.”

假設(shè)你在颶風(fēng)警報(bào)區(qū)開了一家建筑用品公司,所有人都來買膠合板(一種裝修常用的板材)。錯(cuò)誤的做法是將標(biāo)語寫成:“為了將膠合板賣給真正需要的人,我們漲價(jià)了。”

Good practice would be to raise prices with a sign that says “Our wholesale cost of plywood has increased, and we have to pass the cost along to you. But we have not raised our profit margin.”

要想漲價(jià),正確的做法是將標(biāo)語寫成:“我們的膠合板批發(fā)成本上漲了,不得不把成本轉(zhuǎn)嫁給你們。但是我們的利潤并沒有增加。”

Thaler and his colleagues devised the dictator game, an experimental tool that has been used in numerous studies to measure attitudes to fairness in different groups of people around the world.

塞勒和他的同事還設(shè)計(jì)了“獨(dú)裁者博弈”,這個(gè)實(shí)驗(yàn)工具被應(yīng)用在大量研究中,用于衡量世界各地的不同群體對(duì)于公平的態(tài)度。

Lack of self-control

自制力缺乏

Thaler has also shed new light on the old observation that New Year’s resolutions can be hard to keep. He showed how to analyze self-control problems using a planner-doer model, which is similar to the frameworks psychologists and neuroscientists now use to describe the internal tension between long-term planning and short-term doing.

新年計(jì)劃難以執(zhí)行是一個(gè)世紀(jì)難題,塞勒還為解決這個(gè)問題提供了新線索。他向人們展示了如何通過“計(jì)劃者-執(zhí)行者模型”分析自控問題,這個(gè)模型與當(dāng)前心理學(xué)家和神經(jīng)科學(xué)家用來解釋長期計(jì)劃與短期執(zhí)行間的矛盾的理論類似。

Succumbing to short-term temptation is an important reason why our plans to save for old age, or make healthier lifestyle choices, often fail. In his applied work, Thaler demonstrated how nudging – a term he coined – may help people exercise better self-control when saving for a pension, as well in other contexts.

我們打算存養(yǎng)老金,想選擇更健康的生活方式,卻經(jīng)常失敗,一個(gè)重要的原因就是我們會(huì)向短期誘惑屈服。在塞勒的應(yīng)用研究中,他展示了如何通過“助推”(他自創(chuàng)的術(shù)語)來幫助人們更好地控制自己存下養(yǎng)老金,以及完成其他事情。

“助推理論”的原理:

缺少思考時(shí)間、習(xí)慣以及失敗的決策意味著即使事實(shí)分析擺在眼前,比如明知健康飲食的好處,我們?nèi)匀豢赡苓x擇漢堡和薯?xiàng)l。

We're hungry, we're in a hurry and burger and chips is what we always buy.

我們很餓,很著急,而漢堡薯?xiàng)l是我們一直購買的食物。

Nudge theory takes account of this, based as it is on the simple premise that people will often choose what is easiest over what is wisest.

助推理論考慮到了這點(diǎn),人們往往會(huì)做出最容易的選擇,而不是最明智的選擇,該理論就是建立在這個(gè)簡單前提之上。

Tests have shown that putting healthier foods on a higher shelf increases sales.

測(cè)試表明,將更健康的食品擺放在更高的貨架上,銷量會(huì)增加。

The food is more likely to be in someone's eye line and therefore "nudge" that person towards the purchase - whether they had any idea about the obesity argument or not.

擺放在高層貨架上的食物更容易進(jìn)入消費(fèi)者的視線,因此會(huì)“助推”人們購買,不論他們是否了解關(guān)于肥胖癥問題。

綜合《華盛頓郵報(bào)》、《福布斯》、BBC、《新京報(bào)》、《每日經(jīng)濟(jì)新聞》

編譯:董靜

審校:yaning

上一篇 : 職場(chǎng)高手絕不會(huì)自曝的12件事

下一篇 :

分享到

關(guān)注和訂閱

關(guān)于我們 | 聯(lián)系方式 | 招聘信息

電話:8610-84883645

傳真:8610-84883500

Email: languagetips@chinadaily.com.cn